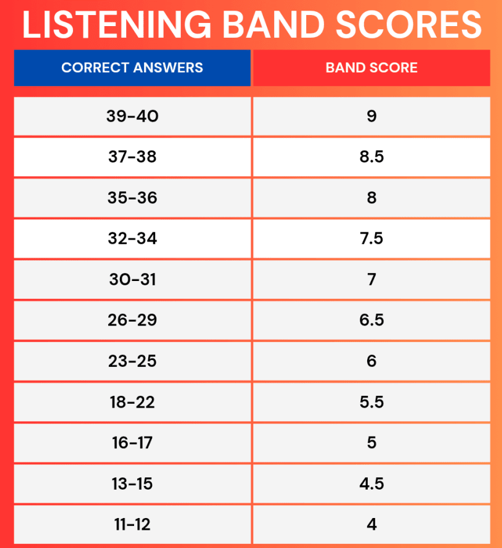

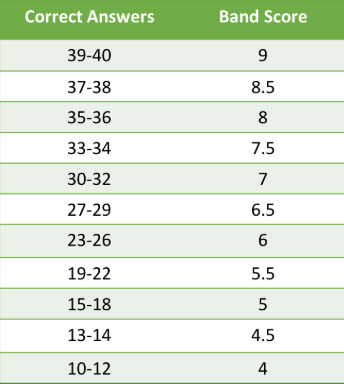

Listening Module

SECTION 1 Questions 1-10

Complete the notes below

Write ONE WORD AND/OR A NUMBER for each answer.

Reading Module [60 Minutes]

Reading Passage 1

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-13, which are based on the Reading Passage 1 below.

Why Are Finland’s Schools Successful?

The country's achievements in education have other nationas doing their homework

A At Kirkkojarvi Comprehensive School in Espoo, a suburb west of Helsinki, Kari Louhivuori, the school’s principal, decided to try something extreme by Finnish standards. One of his sixth-grade students, a recent immigrant, was falling behind, resisting his teacher’s best efforts. So he decided to hold the boy back a year. Standards in the country have vastly improved in reading, math and science literacy over the past decade, in large part because its teachers are trusted to do whatever it takes to turn young lives around. ‘I took Besart on that year as my private student,’ explains Louhivuori. When he was not studying science, geography and math, Besart was seated next to Louhivuori’s desk, taking books from a tall stack, slowly reading one, then another, then devouring them by the dozens. By the end of the year, he had conquered his adopted country’s vowel-rich language and arrived at the realization that he could, in fact, learn.

B This tale of a single rescued child hints at some of the reasons for Finland’s amazing record of education success. The transformation of its education system began some 40 years ago but teachers had little idea it had been so successful until 2000. In this year, the first results from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), a standardized test given to 15-year-olds in more than 40 global venues, revealed Finnish youth to be the best at reading in the world. Three years later, they led in math. By 2006, Finland was first out of the 57 nations that participate in science. In the latest PISA scores, the nation came second in science, third in reading and sixth in math among nearly half a million students worldwide.

C In the United States, government officials have attempted to improve standards by introducing marketplace competition into public schools. In recent years, a group of Wall Street financiers and philanthropists such as Bill Gates have put money behind private-sector ideas, such as charter schools, which have doubled in number in the past decade. President Obama, too, apparently thought competition was the answer. One policy invited states to compete for federal dollars using tests and other methods to measure teachers, a philosophy that would not be welcome in Finland. ‘I think, in fact, teachers would tear off their shirts,’ said Timo Heikkinen, a Helsinki principal with 24 years of teaching experience. ‘If you only measure the statistics, you miss the human aspect.’

D There are no compulsory standardized tests in Finland, apart from one exam at the end of students’ senior year in high school. There is no competition between students, schools or regions. Finland’s schools are publicly funded. The people in the government agencies running them, from national officials to local authorities, are educators rather than business people or politicians. Every school has the same national goals and draws from the same pool of university-trained educators. The result is that a Finnish child has a good chance of getting the same quality education no matter whether he or she lives in a rural village or a university town.

E It’s almost unheard of for a child to show up hungry to school. Finland provides three years of maternity leave and subsidized day care to parents, and preschool for all five-year-olds, where the emphasis is on socializing. In addition, the state subsidizes parents, paying them around 150 euros per month for every child until he or she turns 17. Schools provide food, counseling and taxi service if needed. Health care is even free for students taking degree courses.

F Finland’s schools were not always a wonder. For the first half of the twentieth century, only the privileged got a quality education. But In 1963, the Finnish Parliament made the bold decision to choose public education as the best means of driving the economy forward and out of recession. Public schools were organized into one system of comprehensive schools for ages 7 through 16. Teachers from all over the nation contributed to a national curriculum that provided guidelines, not prescriptions, for them to refer to. Besides Finnish and Swedish (the country’s second official language), children started learning a third language (English is a favorite) usually beginning at age nine. The equal distribution of equipment was next, meaning that all teachers had their fair share of teaching resources to aid learning. As the comprehensive schools improved, so did the upper secondary schools (grades 10 through 12). The second critical decision came in 1979, when it was required that every teacher gain a fifth-year Master’s degree in theory and practice, paid for by the state. From then on, teachers were effectively granted equal status with doctors and lawyers. Applicants began flooding teaching programs, not because the salaries were so high but because autonomous decision making and respect made the job desirable. And as Louhivuori explains, ‘We have our own motivation to succeed because we love the work.’

Reading Passage 1

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 14-26, which are based on the Reading Passage 2 below.

Smart Textiles and Wearable Power

A. Smart textiles—fabrics embedded with electronic components—are transforming how people interact with clothing and the environment. Once limited to novelty garments, smart textiles now encompass serious applications in healthcare, sport, military and occupational safety. Innovations combine conductive threads, flexible sensors and miniature power sources to create garments that monitor physiological signals, adapt to environmental conditions, or communicate with other devices. The shift from prototype to practical deployment has accelerated as manufacturing methods improve and interdisciplinary teams address integration challenges.

B. In healthcare, wearable textiles provide continuous monitoring of vital signs such as heart rate, respiration and temperature. For patients with chronic conditions, garments capable of transmitting data to clinicians can enable earlier intervention and remote care models that reduce hospital admissions. In rehabilitation, sensor-laden garments measure range of motion and gait patterns, informing personalised therapy. Importantly, textile-based sensors are often more comfortable and less stigmatizing than adhesive patches or obtrusive monitors and can encourage adherence to monitoring regimes.

C. Athletes and fitness enthusiasts benefit from embedded sensors that track performance metrics in real time. Data on cadence, muscle activation and localised temperature help coaches and physiotherapists tailor training plans and prevent injury. Beyond monitoring, active textiles can modulate thermal properties—phase-change materials and adaptive insulation layers respond to temperature changes, enhancing comfort and reducing energy use in heating or cooling systems when garments interface with buildings or microclimates. Commercial products already use these principles in performance wear and smart outerwear.

D. Military and first-responder applications emphasise durability and integrated functionality. Fabrics that detect chemical agents, monitor soldier biometrics, or provide haptic navigation cues can increase survivability and situational awareness. Similarly, occupational garments for firefighters or mine workers integrate temperature sensors and passive cooling channels that protect wearers in extreme environments. These domain-specific textiles must meet rigorous standards for washing, abrasion resistance and electrical safety; meeting these standards remains a non-trivial engineering task.

E. Powering smart textiles remains a central challenge. Traditional batteries are bulky and rigid compared to fabric substrates, prompting research into flexible batteries, supercapacitors and energy harvesting. Piezoelectric fibres generate electricity from motion, thermoelectric materials convert heat differentials into power, and photovoltaic coatings harvest light on sun-exposed fabric surfaces. Hybrid approaches—combining small flexible storage with intermittent harvesting—are likely to underpin practical designs for many applications.

F. Manufacturing scalability is improving. Techniques such as embroidery-based conductive stitching, printed electronics on textile substrates and roll-to-roll processing enable higher throughput and lower unit costs. However, integrating electronics introduces new failure modes: seams and assemblies can suffer cyclic bending, laundering can degrade conductive paths, and connectors remain vulnerable. Manufacturers invest in encapsulation methods, stretchable interconnects and washable designs to mitigate these issues and extend product lifetimes.

G. Privacy, data security and ethical questions accompany the proliferation of garments that collect personal data. Health and location data transmitted by clothing raise concerns about consent, data ownership and potential misuse by employers or insurers. Robust encryption, local data processing that minimises transmission, and regulatory safeguards are essential. Public acceptance hinges on transparent governance, informed consent and clear demonstration of benefit-to-risk ratios for users.

H. Sustainability considerations loom large. Embedding electronics complicates recycling and raises questions about e-waste. Designers explore modularity—removable electronic modules that extend product life—or biodegradable conductive materials that reduce environmental impact. Lifecycle assessments that account for additional resource use, potential energy savings from adaptive garments, and end-of-life disposal are becoming standard practice for responsible development.

I. Several pilot projects illustrate practical pathways to adoption. Hospital trials have deployed sensor-embedded shirts to monitor cardiac patients recovering at home, reporting arrhythmias to clinicians and reducing emergency visits. Retail partnerships are exploring rental and take-back schemes for expensive smart garments, combining circular-economy principles with consumer access. Start-ups collaborate with textile mills to prototype fabrics with built-in sensing layers that withstand industrial washing, demonstrating that supply-chain integration is feasible with investment.

J. Economic models for smart textiles vary by application. High-value domains—medical monitoring, elite sport, military use—offer clear institutional purchasers and willingness-to-pay, supporting premium pricing. Mass-market consumer applications depend on cost reductions and demonstrable utility; product differentiation and bundled services (data analytics, care platforms) can create recurring revenue. Insurers and healthcare systems could underwrite devices if evidence shows net savings, creating a pathway for wider adoption in healthcare contexts.

K. Standards and interoperability remain nascent but growing. Consortia of manufacturers, health providers and regulators work to define testing protocols for sensor accuracy, washability, electromagnetic safety and data formats. Interoperability standards will be crucial to avoid vendor lock-in and ensure devices integrate with clinical information systems. Certification schemes may evolve to guarantee safety and privacy properties, building consumer trust and clarifying liability in cross-supplier ecosystems.

L. As standards mature and interdisciplinary collaboration accelerates, smart textiles will likely expand beyond niche applications into mainstream markets. Success depends not only on technical breakthroughs but on regulatory clarity, sustainable design and business models that align stakeholder interests. If these elements converge, clothing may become an unobtrusive platform for health, comfort and connectivity, integrating seamlessly into daily life while preserving human dignity and environmental responsibility.

Reading Passage 3

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 27-40, which are based on the Reading Passage 3 below.

The Swiffer

For a fascinating tale about creativity, look at a cleaning product called the Swiffer and how it came about, urges writer Jonah Lehrer. In the story of the Swiffer, he argues, we have the key elements in producing breakthrough ideas: frustration, moments of insight and sheer hard work. The story starts with a multinational company which had invented products for keeping homes spotless, and couldn’t come up with better ways to clean floors, so it hired designers to watch how people cleaned. Frustrated after hundreds of hours of observation, they one day noticed a woman do with a paper towel what people do all the time: wipe something up and throw it away. An idea popped into lead designer Harry West’s head: the solution to their problem was a floor mop with a disposable cleaning surface. Mountains of prototypes and years of teamwork later, they unveiled the Swiffer, which quickly became a commercial success.

Lehrer, the author of Imagine, a new book that seeks to explain how creativity works, says this study of the imagination started from a desire to understand what happens in the brain at the moment of sudden insight. ‘But the book definitely spiraled out of control,’ Lehrer says. ‘When you talk to creative people, they’ll tell you about the ‘eureka’* moment, but when you press them they also talk about the hard work that comes afterwards, so I realised I needed to write about that, too. And then I realised I couldn’t just look at creativity from the perspective of the brain, because it’s also about the culture and context, about the group and the team and the way we collaborate.’

When it comes to the mysterious process by which inspiration comes into your head as if from nowhere, Lehrer says modern neuroscience has produced a ‘first draft’ explanation of what is happening in the brain. He writes of how burnt-out American singer Bob Dylan decided to walk away from his musical career in 1965 and escape to a cabin in the woods, only to be overcome by a desire to write. Apparently ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ suddenly flowed from his pen. ‘It’s like a ghost is writing a song,’ Dylan has reportedly said. ‘It gives you the song and it goes away.’ But it’s no ghost, according to Lehrer.

Instead, the right hemisphere of the brain is assembling connections between past influences and making something entirely new. Neuroscientists have roughly charted this process by mapping the brains of people doing word puzzles solved by making sense of remotely connecting information. For instance, subjects are given three words – such as ‘age’, ‘mile’ and ‘sand’ – and asked to come up with a single word that can precede or follow each of them to form a compound word. (It happens to be ‘stone’.) Using brain-imaging equipment, researchers discovered that when people get the answer in an apparent flash of insight, a small fold of tissue called the anterior superior temporal gyrus suddenly lights up just beforehand. This stays silent when the word puzzle is solved through careful analysis. Lehrer says that this area of the brain lights up only after we’ve hit the wall on a problem. Then the brain starts hunting through the ‘filing cabinets of the right hemisphere’ to make the connections that produce the right answer.

Studies have demonstrated it’s possible to predict a moment of insight up to eight seconds before it arrives. The predictive signal is a steady rhythm of alpha waves emanating from the brain’s right hemisphere, which are closely associated with relaxing activities. ‘When our minds are at ease-when those alpha waves are rippling through the brain – we’re more likely to direct the spotlight of attention towards that stream of remote associations emanating from the right hemisphere,’ Lehrer writes. ‘In contrast, when we are diligently focused, our attention tends to be towards the details of the problems we are trying to solve.’ In other words, then we are less likely to make those vital associations. So, heading out for a walk or lying down are important phases of the creative process, and smart companies know this. Some now have a policy of encouraging staff to take time out during the day and spend time on things that at first glance are unproductive (like playing a PC game), but day-dreaming has been shown to be positively correlated with problem-solving. However, to be more imaginative, says Lehrer, it’s also crucial to collaborate with people from a wide range of backgrounds because if colleagues are too socially intimate, creativity is stifled.

Creativity, it seems, thrives on serendipity. American entrepreneur Steve Jobs believed so. Lehrer describes how at Pixar Animation, Jobs designed the entire workplace to maximise the chance of strangers bumping into each other, striking up conversations and learning from one another. He also points to a study of 766 business graduates who had gone on to own their own companies. Those with the greatest diversity of acquaintances enjoyed far more success. Lehrer says he has taken all this on board, and despite his inherent shyness, when he’s sitting next to strangers on a plane or at a conference, forces himself to initiate conversations. As for predictions that the rise of the Internet would make the need for shared working space obsolete, Lehrer says research shows the opposite has occurred; when people meet face-to-face, the level of creativity increases. This is why the kind of place we live in is so important to innovation. According to theoretical physicist Geoffrey West, when corporate institutions get bigger, they often become less receptive to change. Cities, however, allow our ingenuity to grow by pulling huge numbers of different people together, who then exchange ideas. Working from the comfort of our homes may be convenient, therefore, but it seems we need the company of others to achieve our finest ‘eureka’ moments.

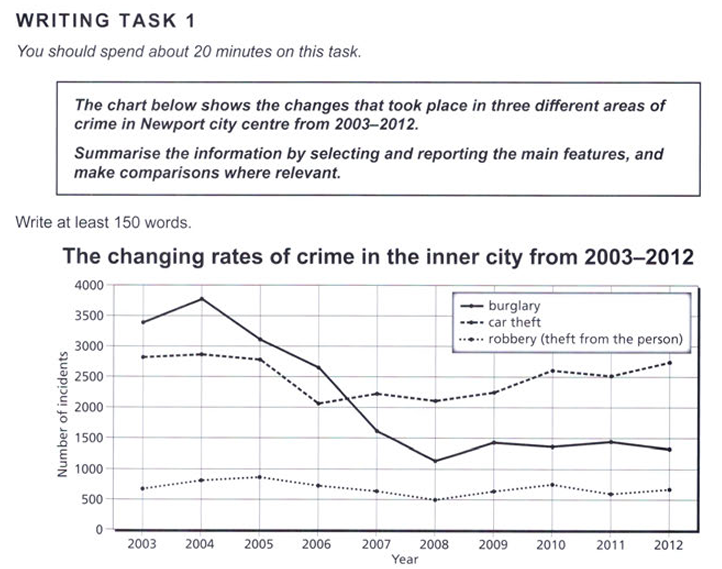

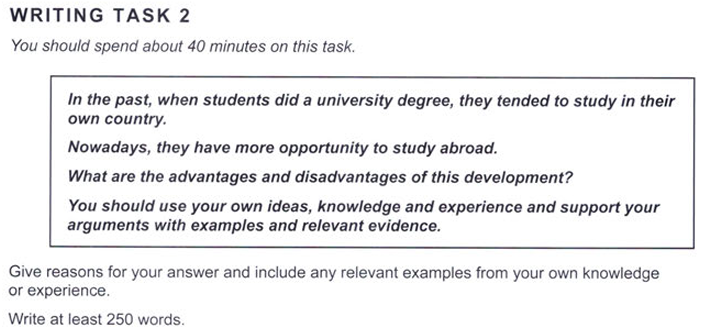

Writing Module [60 Minutes]

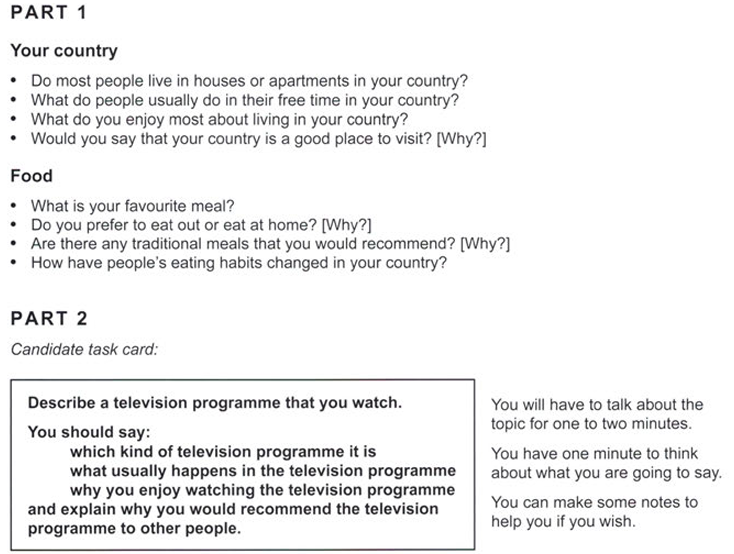

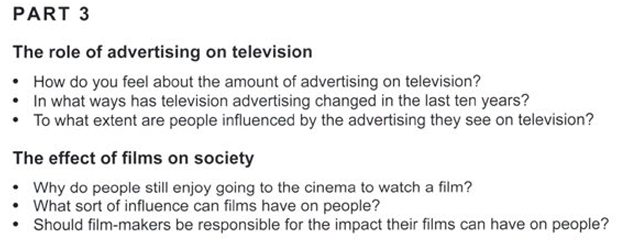

Speaking Module

Get Your Writing and Speaking Skills Assessed by Our British Council Trained Experts Here