The Saiga Antelope

In 1993, more than a million saiga antelope crowded the steppes of Central Asia. However, by 2004 just 30,000 remained, many of them female. The species had fallen prey to relentless poaching – with motorbikes and automatic weapons – in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse. This 97% decline is one of the most dramatic population crashes of a large mammal ever seen. Poachers harvest males for their horns, which are used in fever cures in traditional Chinese medicine. The laughter is embarrassing for conservationists. In the early 1990s, groups such as WWF actively encouraged the saiga hunt, promoting its horn as an alternative to the horn of the endangered rhino. “The saiga was an important resource, well managed by the Soviet Union,” says John Robinson, at the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) in New York City, US. “But with the breakdown of civil society and law and order, that management ceased.”

Have Researchers Created Synthetic Life at the J. Craig Venter Institute?

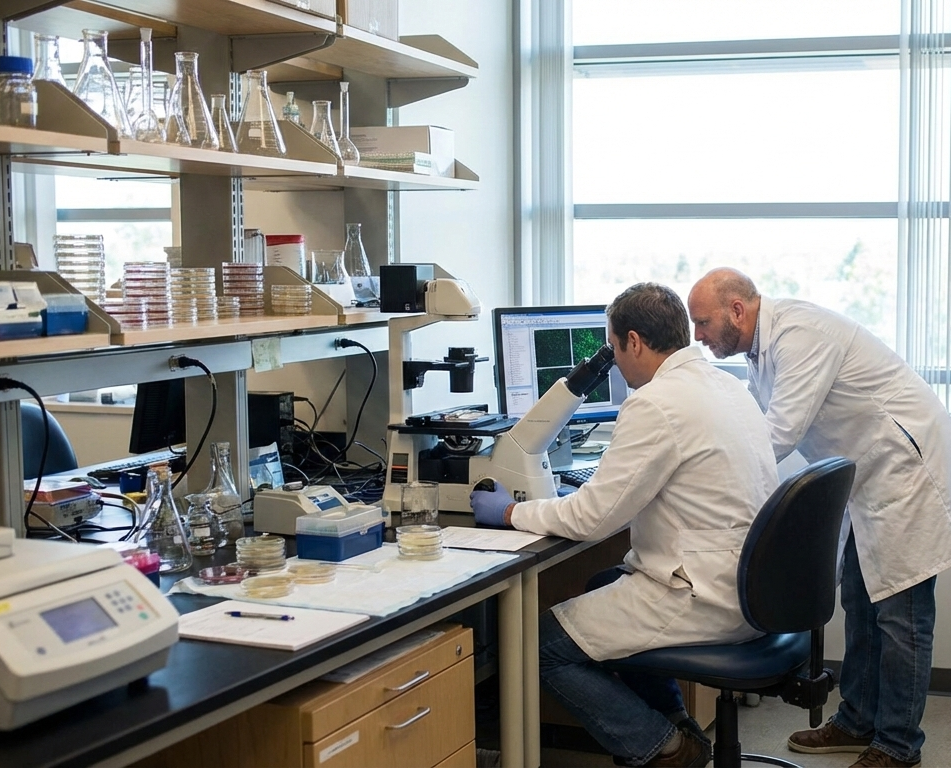

Researchers often insert a gene or two into an organism in order to make it do something unique. For example, researchers inserted the insulin gene into bacteria in order to make them produce human insulin. However, researchers at the J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI) in Rockville, MD, have now created organisms that contain a completely synthetic genome. This synthetic genome was designed by computer, resulting in the ‘first self-replicating species… whose parent is a computer,’ as stated by Dr. Venter, the lead scientist on this project.

In essence, the JCVI scientists took the genome of one bacterial species, M. mycoides, synthesized it from scratch, and then transplanted it into a different bacterial species, M. capricolum. The DNA was synthesized as a series of cassettes, or pieces, spanning roughly 1080 bases (the chemical units that make up DNA) each. These cassetes were then painstakingly assembled together and slowly input into the M. capricolum species.

The JVCI researchers also included several ‘watermarks’ in the synthetic genome. Because DNA contains introns, which are non-expressed spans of DNA, as well as exons, which are expressed spans of DNA, much of the code can be altered without affecting the final organism. Also, the four bases of the DNA code – A, C, G, and T – can combine into triplets to code for 20 amino acids (the chemical units of which protein is composed), as well as start and stop instructions for gene expression. These amino acids are designated by single alphabetical letters; for example, tryptophan is designated by the letter W. Thus, by using the amino acid ‘alphabet,’ the JCVI researchers were able to insert sequences of DNA that were specifically designed to spell out the names of study authors, project contributors, web addresses, and even include quotations from James Joyce, and Richard Feynman. Such engineering helped clarify that the M. capricolum genome is completely synthetic and not a product of natural bacterial growth and replication.

Over one mill;ion total bases were inserted into M. capricolum. The final result was a bacterial cell that originated from M capricolum, but behaved like and expressed the proteins of M. mycoides. This synthetic M. mycoides bacterium was also able to self-replicated, a fundamental quality of life.

The demonstration that completely synthetic genomes can be used to start synthetic life promises other exciting discoveries and technologies. For example, photosynthetic algae could be transplanted with genomes that would enable these organisms to produce biofuel. In fact, the ExxonMobil Research and Engineering Company has already worked out an agreement with Synthetic Genomics, the company that helped fund the JCVI research team, to start just such a project.

While some researchers agree that the technical feat of the JCVI team is astounding, detractors point to the difficulty of creating more complicated organisms from scratch. Other researchers point to the fact that some biofuels are already being produced by microorganisms via the genetic engineering of only a handful of genes. And Dr. David Baltimore, a leading geneticist at CalTech, has countered the significance of the work performed by the JCVI research team, stating that its lead researcher, Dr. Venter, ‘… has not created life, only mimicked it.’

Alaskans’ vitamin D production slows to a halt

Interested people are needed to participated in a one-year study to assess the effects of long dark winters on the vitamin D and calcium levels of Fairbanks residents.

So began a recruitment poster Meredith Tallas created 25 years ago. Now living in Oakland, California, Tallas was a University of Alaska Fairbanks student in 1983 who wanted to study how levels of a vitamin related to sun exposure fluctuated in people living so far from the equator.

‘The most obvious vitamin to study in Alaska is vitamin D, because of the low light in winter,’ Tallas said recently over the phone from her office in Berkely.

Forty-seven people responded to Tallas’ 1983 request, and her master’s project was underway. By looking at the blood work of those Fairbanks residents every month and analyzing their diets, she charted their levels of vitamin D, which our skin magically produces after exposure to a certain amount of sunshine. We also get vitamin D from foods, such as vitamin-D enriched milk and margarine, and fish (salmon are a good source). Vitamin D is important for prevention of bone diseases, diabetes and other maladies.

If you live at a latitude farther north than about 42 degrees (Boston, Detroit, or Eugene, Oregon), the sun is too low on the horizon from November through February for your skin to produce vitamin D, according to the National Institutes of Health. Tallas also saw another potential Alaska limitation on the natural pathway to vitamin D production.

‘Most outdoor activities require covering all but the face and hands approximately seven months of the year,’ she wrote in her thesis. ‘During the summer months residents keep much of their bodies clothed because of the persistent and annoying mosquitoes and biting flies and because of this, an Alaskan summer suntan becomes one of the face and hands.’

But even over bundled people like Alaskans show signs of enhanced vitamin D production from the sun. Tallas found the highest levels of vitamin D in the Fairbanks volunteers’ blood in July, and the lowest levels in March. Tallas attributed the July high occurring about a month after summer solstice to the time needed for the body’s processing of sunlight and the conversion to vitamin D.

In Tallas’ study, volunteers showed low levels of vitamin D in winter months, but most got sufficient doses of vitamin D from sources other than the sun. Tallas also found that males had an average of 16 percent more vitamin D in their blood throughout the study, which she attributed in part to men being outside more.

In charting an average for people’s time outside (you can’t convert sunlight to vitamin D through windows), she found December was the low point of sunlight exposure, when sun struck the skin of her volunteers for less than 20 minutes per day. People spent an average of more than two hours exposed to Alaska sunlight in June and July. They seemed to hunker down in October, when time outside in the sun dropped to about half an hour after almost two hours of daily sun exposure in September.

Vitamin D levels in the volunteers’ blood dropped in August, September, October, November, December, January, February, and March, but Tallas saw an occasional leap in midwinter. ‘When someone had gone to Hawaii, we could see, very exactly, a significant spike in their vitamin D levels,’ Tallas said. ‘The only surprise was how it came a month or two after.’

In her thesis, Tallas wrote that a midwinter trip to somewhere close to the equator would be a good thing for boosting Alaskans’ vitamin D levels. ‘Presuming that an individual’s lowest circulating vitamin D level is found in March or April, such trips could potentially have a very significant effect in improving late winter vitamin D status,’ she wrote in her thesis. ‘Unfortunately a majority of Alaskan residents do not take such trips often.’ An easy alternative for Alaskans not travelling southward during the winter is eating food rich in vitamin D or taking vitamin D supplements, Tallas said.

The IELTS Evidence Hunter: Your Ultimate Guide to Conquering True/False/Not Given